Something there is that doesn’t love a wall, wrote the poet. And lack of love for the Cold War Wall in Berlin was the essence of an absence of love. It marked instead the cruelest separation. The animosity at that time between the communist and democratic world was— to borrow a phrase from the time— written in triplicate. We don’t use that expression any more because people don’t make carbon copies, but they did then— 1967, which marked my intro to Europe. You needed extra pages to get it all out. So I’ll make this one in three copies.

Copy One:

Three of us Americans and one Dane drove the barbed wire corridor that summer into East Germany and paid a visit to the divided city of Berlin. It was at this locale that I performed the most definite political act of my life by urinating in the most defiant stance possible smack dab on the Berlin Wall.

It was not an intentional act. Mind you, I didn’t book passage on an Icelandic Air Line economy flight to accomplish that objective. It turned into a spur-of-the-moment gesture beginning innocently enough by discovering the excellence of German beer. It occurred after absorbing a gargantuan quantity, and no place to displace it. The urge to void the excess lager caught up with  traveling companion, Bob, and self as we wandered at dusk in a back street of the western sector. The street ended (seeming symbolically) at some mounds of rubble piled high in front of The Wall. Since it was old rubble with shrubbery growing out of it, we decided to utilize it for cover. But as I clambered up over one those piles of war waste, out of sight of the street, I there met— face-to-face, just a few meters farther, already in shadow— The Wall.

traveling companion, Bob, and self as we wandered at dusk in a back street of the western sector. The street ended (seeming symbolically) at some mounds of rubble piled high in front of The Wall. Since it was old rubble with shrubbery growing out of it, we decided to utilize it for cover. But as I clambered up over one those piles of war waste, out of sight of the street, I there met— face-to-face, just a few meters farther, already in shadow— The Wall.

It was then I felt another deeper urge and so uttered my declaration. It falls in line with warrior history: before an intended act of defiance, an oath of intention must be sworn or the act doesn’t count. Well, my oath wasn’t as timeless as “Give me liberty or give me death,” nor “I only regret I have but one life to give to my country.” What I believe I said to Bob was, “I’m going to piss on that son-of-a bitch.”

Which act, after clambering over another pile to reach the foot of the wall, was duly accomplished.

It was at a point off to the right, I recall, within sight of the solitary glow of Checkpoint Charlie. Light fading into dusk, I was just able to make out a coil of that eternal commie razor wire lying at the foot of the wall. Just before making my final statement and letting go, a chilling thought grabbed my mind: “Damn, what if that wire is electrified?”

Thankful that it wasn’t, I finished the action and zipped— first my pants, then self, zipping off stumbling across the crumbled landscape that recalled carpet bombing and carnage, clambering back toward our van while glancing over a wary shoulder.

Copy Two:

As Twisty McFate would have it, several years after Ronald Reagan’s injunction to Mr. Gorbachev to tear down that abysmal monument to political incarceration, that eyesore of humanity, it actually came down— graffiti and all— in 1989.

Nine years later, 2008, I happened to be sharing a German dinner in Vancouver, Washington, with a friend. In the process of yarning about Germany, I learned that that very friend, also named Bob, was stationed in Berlin in that very same summer of 1967. This was definitely a noteworthy addition to my collection of koinkidinks. Not only were we both there in Berlin, but the coincidence was amplified when, after a couple more bites of schnitzel, Bob reported having performed guard duty right there at Checkpoint Charlie. Furthermore, he could’ve actually been on duty, theoretically, at the moment I was busy defying fate with my liberation urination.

Nine years later, 2008, I happened to be sharing a German dinner in Vancouver, Washington, with a friend. In the process of yarning about Germany, I learned that that very friend, also named Bob, was stationed in Berlin in that very same summer of 1967. This was definitely a noteworthy addition to my collection of koinkidinks. Not only were we both there in Berlin, but the coincidence was amplified when, after a couple more bites of schnitzel, Bob reported having performed guard duty right there at Checkpoint Charlie. Furthermore, he could’ve actually been on duty, theoretically, at the moment I was busy defying fate with my liberation urination.

After relating the story of my intimacy with the wall, I added the suspicion of the danger that had been nagging over the years. “I suppose,” I told Bob, “there were probably a dozen rifles trained on me at that moment.”

His expression was half-bemused, half-horrified, as he nodded affirmatively and simply said: “Yeah.” He could have said, “Duh! How dumb do you have to be to even ask?”

I never doubted the possibility of the severe consequences I was spared. Over the years, I learned how Berlin had been mangled first by Nazi and then by Stasi. I had other friends stationed in Berlin who described the serious show-down military tactics from both sides of The Wall. Ferret flights across borders provoking fire power and neurotic surveillance, a private course on that oppression which was capped by a return visit in 2012.

An entire city neighborhood, itself already showing age, were built over the zone of empty boarded buildings that had faced The Wall. Presently, it’s Disneyland with strudel. I remembered the strained atmosphere in 1967, the mood of forced gaiety— the word then used to describe the nervous joy of the western sectors. A tourist haven is now re-constructed in that one-time zone of terror. In 1967 public places were open at night behind shutters where fun, though sounding desperate, was to be heard inside; not much else were the receding lights at Checkpoint Charlie and further darkness on the other side.

An entire city neighborhood, itself already showing age, were built over the zone of empty boarded buildings that had faced The Wall. Presently, it’s Disneyland with strudel. I remembered the strained atmosphere in 1967, the mood of forced gaiety— the word then used to describe the nervous joy of the western sectors. A tourist haven is now re-constructed in that one-time zone of terror. In 1967 public places were open at night behind shutters where fun, though sounding desperate, was to be heard inside; not much else were the receding lights at Checkpoint Charlie and further darkness on the other side.

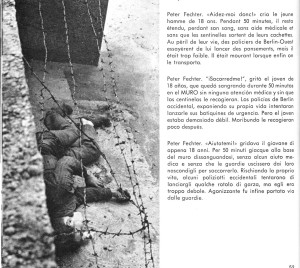

That same Checkpoint was the only reference forty five years later, and so it was difficult to calculate just where I despoiled the wall. But not far from the supposed location, a monument had been erected. It remembers a young man named Peter, gunned down in one of the many attempted escapes over The Wall.

That same Checkpoint was the only reference forty five years later, and so it was difficult to calculate just where I despoiled the wall. But not far from the supposed location, a monument had been erected. It remembers a young man named Peter, gunned down in one of the many attempted escapes over The Wall.

Born in 1943, Peter Fechter was one of the Reich’s jungen engendered for Hitler’s Germany. Born in the cusp of the Reich, his mother doubtlessly got one of those medals the frauen received for bearing another morsel of cannon fodder. Peter missed the glorious celebration of the Third Reich, but instead got to grow up in the miseries of post-war Berlin, and then afterward treated to  Stasi communist rule. No wonder he was desperate to get out. Desperate enough to get shot trying. And then dying as he’d lived, enduring first political agony, and then physical. He bled and cried for help nearly an hour before the cries ceased. Judging by the picture of where the body lay, it could have been that spot, or one similar (recognized by a jog in the wall) on the other side of the niche I utilized.

Stasi communist rule. No wonder he was desperate to get out. Desperate enough to get shot trying. And then dying as he’d lived, enduring first political agony, and then physical. He bled and cried for help nearly an hour before the cries ceased. Judging by the picture of where the body lay, it could have been that spot, or one similar (recognized by a jog in the wall) on the other side of the niche I utilized.

We grew up two years apart, Peter and I. But I grew up to live on the luckier side. The side the Puritans originally went for in the name of freedom. Grew up enjoying post-war prosperity and the luxury of a genuine education for little more than the price of books and a modest entrance fee. Living in a country whose problems included too many people becoming overweight, and certainly not having to fight over a potato in the rubble. Free to travel with my blue passport down a patrolled hundred-kilometer corridor to a city where an 18 year-old kid made a try for his life in a desperate climb to freedom and got shot for his trouble.

We grew up two years apart, Peter and I. But I grew up to live on the luckier side. The side the Puritans originally went for in the name of freedom. Grew up enjoying post-war prosperity and the luxury of a genuine education for little more than the price of books and a modest entrance fee. Living in a country whose problems included too many people becoming overweight, and certainly not having to fight over a potato in the rubble. Free to travel with my blue passport down a patrolled hundred-kilometer corridor to a city where an 18 year-old kid made a try for his life in a desperate climb to freedom and got shot for his trouble.

That wall was only good for the purpose I put to it.

Copy Three:

The true joy over having survived my own Berlin foolishness came to me by a vision, television actually, viewed in a cheap Hong Kong hotel. It was just a couple of notches above flop house accommodations, but it was still our first Hong Kong hotel. And even my wife, who normally sought every regal feature she could get in a hotel, was amused by the Fuji.

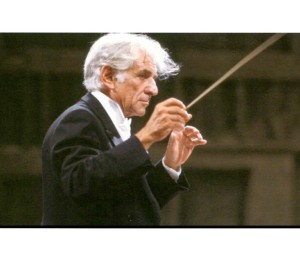

Christmas, 1990. Watching on what might have been the last fuzzy black-and-white screen in creation, there was broadcast the celebration in Berlin of the mauer fall, or wall fall. (Thanx Mr.  Gorbachev for taking Ronnie’s advice.) On that miserable little screen I’m watching a concert performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony recorded at the Tor Gate with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. And it was conducted by Leonard Bernstein. His last— or close to it— his last widely broadcast concert. The sentimental power of it was quite memorable.

Gorbachev for taking Ronnie’s advice.) On that miserable little screen I’m watching a concert performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony recorded at the Tor Gate with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. And it was conducted by Leonard Bernstein. His last— or close to it— his last widely broadcast concert. The sentimental power of it was quite memorable.

Alright, anyone who knows me knows how gooey I can get about Ludwig in the first place, but this was a moment of super-goo. Ramifications kept multiplying in my mind, and still do. First and most obvious, the concert itself, given in celebration of the demise of one of the most despised symbols of oppression in the world at that time. We freedom fighters were united in our joy at seeing it torn down, although I don’t know how many of them actually marked it like a German Shepherd. But the circumstances sent so many vibes out my way, there in Hong Kong, it was hard to catch them all.

(As an aside, respect is due to Asian people and their inordinate love of music. And as for Ludwig’s Ninth, they play it ritually during the holidays as often it seems as Americans play Jingle Bells.)

And the symphony itself needs no further compliment from me to whom it is church— that methodically spirited, monumentally thundering progression to a seemingly divine resolution. Seeing that event historically or politically, it represented triumph heaped upon triumph. First, for the composer who once gave the finger to Napoleon for his imperialism, and then later in history had his music ironically associated with the Third Reich. An artist so pure in his work he was obnoxious about it. A composer who dedicated his final masterpiece to the theme of brotherly love, and then gets to be associated with world-class Nazis thugs. I firmly believe if that same man, who cancelled a dedication to a usurping emperor, were to be walking in Berlin in 1967— well, I can’t help but feel that he might’ve been tempted to join the urination-on-the-mauer ceremony.

And the symphony itself needs no further compliment from me to whom it is church— that methodically spirited, monumentally thundering progression to a seemingly divine resolution. Seeing that event historically or politically, it represented triumph heaped upon triumph. First, for the composer who once gave the finger to Napoleon for his imperialism, and then later in history had his music ironically associated with the Third Reich. An artist so pure in his work he was obnoxious about it. A composer who dedicated his final masterpiece to the theme of brotherly love, and then gets to be associated with world-class Nazis thugs. I firmly believe if that same man, who cancelled a dedication to a usurping emperor, were to be walking in Berlin in 1967— well, I can’t help but feel that he might’ve been tempted to join the urination-on-the-mauer ceremony.

And the frosting on that exquisite cake was the conductor, Leonard Bernstein himself. That same conductor— leading the Berlin Philharmonic with his familiar flourish under the tower gate where the wall departed— was a Jew. And not just any Jew. Possibly the most renowned conductor and composer made in America.

And the frosting on that exquisite cake was the conductor, Leonard Bernstein himself. That same conductor— leading the Berlin Philharmonic with his familiar flourish under the tower gate where the wall departed— was a Jew. And not just any Jew. Possibly the most renowned conductor and composer made in America.

As a gesture toward liberty itself, Lennie took one in this performance. He took the liberty of changing the title, rewording Schiller’s Ode to Joy and substituting the word Freiheit (freedom) for the word Freude (joy). A worthy substitution, although a combination of the two terms work as well as, say, the joy of freedom. Lenny felt that, under the circumstances, Ludwig would have approved the change. I certainly do.

And that’s where this whole scenario— seeing the Ninth being performed not far from where Peter Fechter bought it and viewed from a funky hotel in Hong Kong— it all came together magnificently. Just like Ludwig’s music. You have little impish doodles, scherzi, light diddling passages that could be background music for a fool goofy enough to defy fate with a childish stunt smack dab on the hottest contested international border of the time.

From those little dalliances, the notes, the tones range upward to the lofty and lordly. A friend of mine knew a woman who sang in the chorus of the Ninth; she reported seeing tears in every eye of her fellow chorus members at the height of that peaking sequence of triumph at the end, chorus and instruments in full measure, extolling brotherhood— and freedom— for the millions.

Gooey every time for me, even after hearing it uncountable times before. That familiar methodical monumental progression to its firm resolution, with orchestra and chorus on full throttle— the complete consort dancing together, as the poet says— and that celebration of the wall fall led by a most distinguished surviving descendant of the Holocaust.

I’d urinate— even if only verbally— on anything wanting to destroy that glory, that freedom.

JoCo, Thanksgiving Day, 2016

I really enjoy the blog post.Really looking forward to read more.